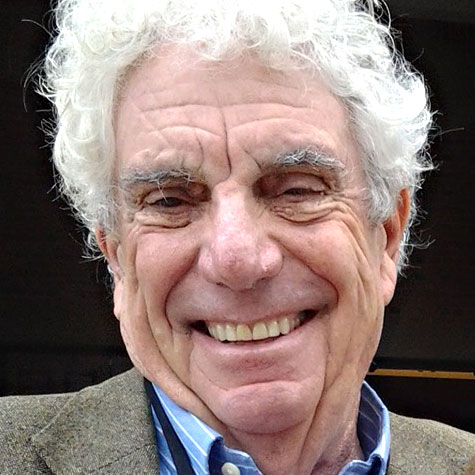

When Ed Guthman died Aug. 30 at the age of 89, the Los Angeles Jewish community lost one of its most distinguished members.

He had been a Pulitzer Prize- winning reporter. As press secretary to Atty. Gen. Robert Kennedy, he braved danger in the South when the federal government forced recalcitrant states to integrate. Before that, he’d faced danger in combat in Italy during World War II.

Ed was an editor at the Los Angeles Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer. He was a beloved journalism professor at USC. He helped create and then headed the Los Angeles City Ethics Commission.

I don’t believe Ed was religious. We never discussed it. Our shared religious background was hardly mentioned when, in 1972, he assigned me to do a story that was of major interest to the Jewish community.

At the time, Republicans were mounting a quiet but intense campaign to persuade Jews to vote for President Richard M. Nixon on the grounds that he was Israel’s best friend. I told Ed I had a connection who might help, Louis Boyar, a cousin who was a major philanthropist, political contributor, supporter of the Jewish community and friend of Golda Meir, the prime minister of Israel.

Ed assigned me the story. I had lunch with Boyar at the Hillcrest Country Club and reported what I had learned. It wasn’t enough, so Ed sent me east, first to the office of Jake Arvey, the retired Chicago political boss and a prominent Jew, and finally to the Israeli Embassy in Washington. The last stop, plus some other interviews, finally gave me enough information to satisfy Ed, and I wrote the story.

Looking back on the incident, what was striking was how little our being Jewish figured into the pursuit of the story, even though it would be widely discussed in the community. My memory of the story is how he urged me on until I got to the bottom of it.

That’s not unusual. A newsroom is a most secular place. In all my years in newsrooms, I can recall discussing religion with only one person, my friend Tim Rutten, a devout, although cynical, Catholic.

Such secularism, by the way, is one reason for journalism’s spotty coverage of religion. The United States is a highly religious country, but this is not reflected on television news or in mainstream publications.

But whether or not he was religious, Ed was a righteous man — although never self-righteous — who approached his tasks with a commitment to social justice, honesty and concern for society’s underdogs. There was something biblical about him, like those prophets who couldn’t let evil pass by without doing or saying something about it.

When he was honored by the Los Angeles City Council for his public service, he said he was grateful to his father, a German Jewish immigrant, for imbuing in him an obligation to serve.

“He always taught us that we had to give something back to this great country and the freedom we enjoy and experience,” he said.

I became friends with Ed at the Times, where he was national editor from 1965 to 1977.

It was a big job. Ed was in charge of a growing network of bureaus around the country, as well as the Washington bureau. In addition, he was responsible for a national desk, which edited the large number of stories that came in each day.

Ed took the best of this work into the daily news meetings, where the managing editor, after hearing the pitches of each of the editors, decided what would go on Page 1. Ed argued fiercely for his stories and was sometimes too intense for a group who seemed to take pride in being calm, laid back and uninvolved.

It was a tumultuous period, and Ed was in the middle of it. The Watts Riot of 1965 ushered in the era, followed by student rebellions in Berkeley and across the country and then demonstrations against the Vietnam War. In the middle of it were the assassinations, first of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and then Ed’s friend, Robert Kennedy. That occurred here in Los Angeles, the night Kennedy won the 1968 California Democratic primary.

Then there was Watergate. Ed’s leadership in the Times coverage and his association with Kennedy earned him a place high on Richard Nixon’s enemies list.

Ed’s office was one of several for editors at one end of the vast newsroom. He didn’t spend a lot of time in the office. When he was in there, he was on the phone with his correspondents around the country and in the Washington bureau.

But much of the time, he roamed through the newsroom, talking to reporters. He respected reporters and was curious about what they were working on and how they were going about it.

That’s how I became friendly with him. I covered politics, and Ed was intensely interested in what I was doing, from state elections to campaigns for City Council. He began arranging with my boss for me to do national stories for him.

In writing this sort of piece for a newspaper, a journalist looks for illuminating anecdotes that in three neat paragraphs can illustrate and explain the subject of a story.

Ed did not lend himself to anecdotes. He was forthright and plain in his speech. For a man of such accomplishment, he was extremely modest. In a business full of men and woman with huge egos, he didn’t boast of glory days of the past.

So I don’t have any great stories about Ed. What I took away from our friendship was a commitment to social justice and to fighting injustice. Long after he left the paper, I tried to carry on his tradition in my own work and, when I became an editor, in the work of my reporters. Many of them knew Ed and were inspired by him, as were his students at USC.

They are Ed’s legacy to journalism and his country.

Until leaving the Los Angeles Times in 2001, Bill Boyarsky worked as a political correspondent, a Metro columnist for nine years and as city editor for three years. You can reach him at bw.boyarsky@verizon.net.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.