The schoolchildren hung on Daniel Saat’s every word as he spoke about orbits, atmospheres, propulsion and moon hopping — not the same as moonwalking.

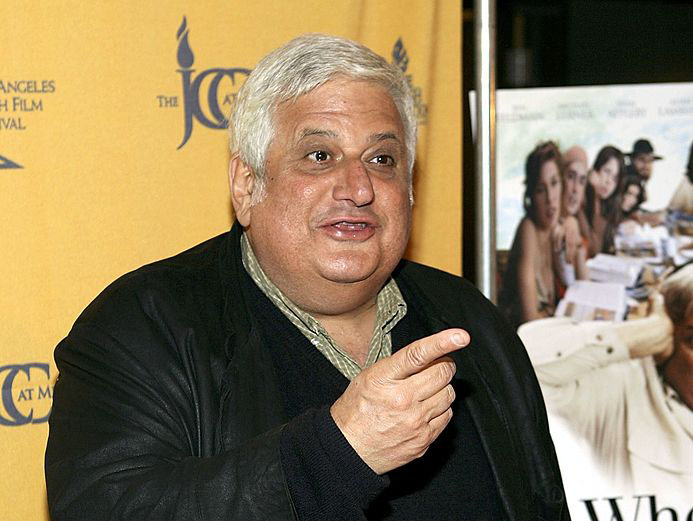

As the director of business development for SpaceIL — Israel’s project to send a micro-spaceship to the moon — Saat and founder Yariv Bash had traveled from Tel Aviv to Los Angeles from Jan. 28 to Feb. 1 on a whirlwind trip organized by Bnei Akiva, the religious Zionist youth movement. Their trip included a visit to about 150 elementary and middle school pupils at Harkham Hillel Hebrew Academy in Beverly Hills.

Handing out prizes to students who asked questions, Saat did his best to describe the spacecraft SpaceIL is building in terms that little nonscientists could understand.

“Our spacecraft is about the size of your washing machine at home,” he said. “The bigger and heavier it is, the more expensive it is, so the smaller we can make our spacecraft, the more efficient and cheaper the ride to outer space will be.”

Bash, a Tel Aviv native, founded Space IL in 2010 as a response to Google’s Lunar X Prize competition, which challenges private companies to land a craft on the surface of the moon, travel 500 meters above, below, or on its surface and send back proof — a video feed — to Earth. The first team to complete the challenge before the end of 2015 will win $20 million. Other cash incentives are included for, among other things, operating at night and landing near an Apollo site.

Bash and Saat are shooting for the top prize, but even if they don’t win, Saat said, SpaceIL intends to land a craft on the moon. That would make Israel the fourth nation to ever successfully complete the 238,900-mile journey, behind the United States, the former Soviet Union and China.

Saat spoke proudly of how cost effectively SpaceIL is traveling to outer space. Comparing it to America’s 1969 moon landing, he asked students to guess how much that mission would cost in today’s dollars. The children threw out guesses: $10 million? $50 million? $100 million? $1 billion?

Nope. The Apollo 11 mission, which cost about $25.4 billion in 1969, would cost closer to $200 billion today, based on numbers provided by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Although SpaceIL doesn’t have to worry about getting a man on the moon, its budget is a meager $36 million. And keeping the spacecraft small, about 300 pounds, by skirting things like a rover, will help keep the project within budget.

Dozens of hands went up throughout SpaceIL’s presentation, as students asked questions about outer space and the project. Jacqueline Englanoff, a Hillel sixth-grader, was intrigued by SpaceIL’s method of sending back information to Earth — antennae, instead of satellites, to help make the relatively small craft a bit lighter.

Yonah Berenson, another sixth-grader, was amused by how the Israeli scientists plan to navigate the surface of the moon once the craft lands. Instead of navigating the required 500 meters using a rover — complete with wheels, which every other competitor is using — SpaceIL will use “the hop,” which involves landing and then taking off again with the fuel remaining in the propulsion system, landing 500 meters away.

“It was very cool,” Berenson said. “I liked how they [said] that the spacecraft was going to hop on the moon — sort of funny.”

The awe that the presentation inspired in the students is a miniature effect of what the SpaceIL team hopes will happen in Israel if it succeeds in the moon landing — a potential Israeli version of the “Apollo effect,” which rejuvenated Americans’ interest in mathematics and engineering following Neil Armstrong’s moonwalk. Saat envisions Jews in Israel and around the world glued to their television sets when SpaceIL makes its trip to the moon — between late 2015 and mid-2016, if Google extends the deadline, which many think it will.

Saat told the students that once the craft leaves Earth’s orbit, it will enter that of the moon, and will be speeding along at an amazing two miles per second. Next, as Bash said, will come the most difficult part: the landing.

“You can’t really simulate it here on earth,” he said.

Slowing the craft down from two miles per second to a speed that will allow it to safely land will be no easy feat, but when the mission reaches that point, years of work and millions of dollars will hinge on the precise execution of a few minutes, or seconds.

“It will be something that only superpowers have done before,” Saat said. “We hope that we won’t join the club of … countries that have crashed things into the moon.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.