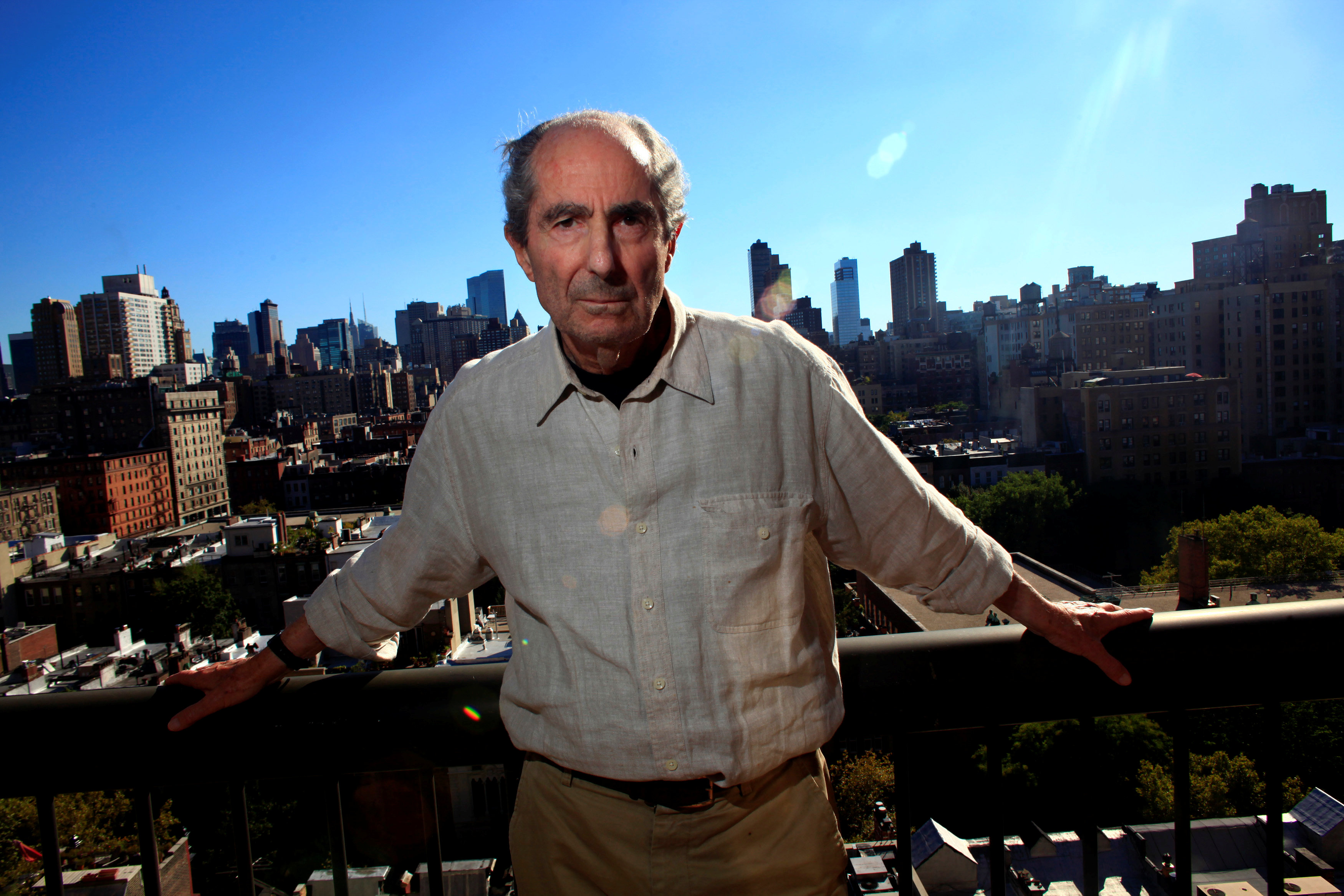

The camera opens on a frazzled Philip Roth.

He is futzing with the horseshoe of hair he has left, rubbing his face and furrowing his unruly brow as a look of supreme unease settles over his face. For a man who recently announced his retirement, he seems a bit stressed. And for a writer who has spent the better part of his life projecting outward, Roth, at first, squirms under the scrutiny of the camera’s gaze.

“In the coming years I have two great calamities to face,” he announces at the beginning of the documentary “Philip Roth: Unmasked” for the PBS “American Masters” series that will air on March 29. “Death and a biography. Let’s hope the first comes first.”

From the outset of his denouement, the newly minted octogenarian — Roth turned 80 on March 19 — has been in the news a lot lately. In November, he told a New York Times reporter, “The struggle with writing is over,” which sent shockwaves through the literary world and effectively commenced his retirement. And over the past few weeks, he made headlines yet again for the many birthday celebrations being held in his honor — in Newark, where he grew up, and New York, where he resides part time, there has been a literary conference, a museum toast, hometown bus tours and even a photography exhibit devoted to his life and oeuvre. Now comes the documentary, also timed to his birthday, which features a chatty and reflective Roth looking back on a life lived through words.

In it, he is as candid, open and charming as ever. Quoting the Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz, Roth observes the truth of his life: “When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.”

It follows then that Roth’s most faithful relationship has been to his work. Other than two brief and really disastrous marriages, he has remained at-least-legally unattached and has never fathered children. In 1983, he told People magazine: “I can’t talk casually about home and family, about good marriages and bad marriages and the relationship between men and women and children and parents. I’ve devoted a life to writing about these things. These are my subjects. I’ve spent years trying to get it right in fiction.”

As many presume is the case with his novels, Roth appears in the film as both narrator and narrative. He is entirely in his element as he recounts tales from his childhood and career trajectory for Italian journalist and French director Livia Manera, and expounds on his foremost passions and preoccupations, which, over eight decades, haven’t changed much: reading, writing, Jewishness and sex continue to ensorcell him. “God, I’m fond of adultery,” Roth says at one point, during a discussion of his 1995 book “Sabbath’s Theater” (his personal favorite). “Aren’t you?”

The author of 31 books, among them at least a dozen bestsellers, is also the recipient of the Pulitzer Prize, the Man Booker Prize, the National Book Award and the PEN/Faulkner Award, to name a few. But among writers of contemporary fiction, perhaps no one is more closely associated (or confused) with his characters as much as Roth. “People have always assumed his characters are him,” writer Nicole Krauss observes in the film.

And Roth offers some delicious and illustrative anecdotes: In 1969, with the release of his career-making “Portnoy’s Complaint,” Roth recalls, “Everything people perceived in Portnoy, they then perceived in me.” One day as he walked near his home, a man shouted at him from across the street: “Philip Roth: Enemy of the Jews!

Roth admits his own life has served as fodder for his fiction, but he prefers to think of this journalistic element as “invent[ing] off of something.” He was influenced in this by another American (Jewish) writer, the incomparable Saul Bellow, who he says, inadvertently gave him permission to draw from his own experience. After reading “The Adventures of Augie March” as a college student, Roth felt free to plumb the depths of his background.

But it wasn’t exactly an exercise in memoir: “I’d have to fight my way to the freedom of drawing upon what I knew,” Roth says. “Life isn’t good enough in some ways. If it was just a matter of putting things down that happened to you, or happened to your friend or happened to your wife, you wouldn’t be a novelist.”

But balancing between truth and fiction can be tricky. He isn’t fond of being called an American Jewish writer, for instance. “I don’t write in Jewish. I write in American,” he says. But that may be a defensive position taken after enduring years of public criticism. From the time “Defender of the Faith,” his first short story was published for The New Yorker, readers held Roth responsible for popularizing Jewish archetypes. “It caused a furor,” Roth remembers of the 1959 publication, “I was being assailed as an anti-Semite and a self-hating Jew. I didn’t even know what it meant.

Even author Jonathan Franzen admits he had a “moralistic response” when he first read Roth. He thought, “Oh, you bad person, Philip Roth,” though he added, “I eventually came to feel as if that was coming out of envy. I wish I could be as liberated … as Roth is. Here’s a person who’s decided he does not care what the world thinks of him. He is not shame-able.”

The widespread perception of the wanton sexuality associated with many of Roth’s novels is a source of some frustration for the author, who spends some time on camera defending specific characters who have been charged with being “sex obsessed.”

“In nine books,” Roth begins, outlining the plot of each one, “there is virtually no sexual experience.” And yet, the characters, he says, “are described repeatedly as sex-obsessed. Well, that’s because Roth is.”

In matters of sexual appetite, at least, his art imitates his life. To that end, he recounted his favorite line from James Joyce’s “Ulysses,” which comes during a scene when the character Leopold Bloom walks to the waterfront to watch a girl and masturbate. “Joyce tells you what’s going on, but you don’t get it — until the next paragraph, Joyce goes: ‘At it again.’ I loved it. I think it should be on my tombstone.”

As Roth wrote in the 2001 novella, “The Dying Animal,” “Sex is all the enchantment required.”

Roth’s candid and sometimes contradictory take on himself, is given added context by friends and colleagues, from fellow writers like Franzen and Krauss to actress Mia Farrow. But the most intelligent and insightful comments come from his biographer, New Yorker critic Claudia Roth Pierpont (no relation), whose book “Roth Unbound” will be published in November.

It was Kafka, she points out, who said, “We should read only those books that bite and sting us,” adding that, for her, Roth is that perfect dose of painful pleasure. “If the book you’re reading does not rouse you with a blow to the head, then why read it? I think that Roth writes books that are meant to rouse you with a blow to the head.”

Roth’s pugnacious prose, however, is fueled by a rather ordinary and peaceful private life. He splits his time between New York City and a country home in Connecticut, where, when he is writing, he writes “every day,” standing up, with “lots of quiet … lots of hours … lots of regularity.” At night, surrounded by his books, the faint silhouette of trees swaying still visible through darkened windows, he likes to read for several hours and listen to music. Once or twice the camera intrudes upon him as he listens to opera or Mahler’s Third Symphony and listens intently, with his whole body, much the way he reads. And it is sheer delight when the camera invites us to watch and listen as Roth reads passages throughout from some of his best-loved works, adding new volume to the voice on the page.

His quieter moments are more frequent now, as Roth confronts his mortality. He says he is afraid of death, but not enraged by its coming. What is hard is that he suffers from chronic back pain, and, like other great writers before him — Ernest Hemingway, Virginia Woolf, Primo Levi — he admits he has contemplated suicide. “Writing turns out to be a dangerous job,” he says. But, “I don’t want to join them.”

Before he dies, though, he plans to reread the authors he admired growing up, among them Conrad, Hemingway, Faulkner and Kafka. And while he swears he’s through with writing himself, hardly any of his friends — or fans — believe him.

Near the end of the film he tells of a recent walk he took near his Connecticut home when he happened upon a wooden sign in a tree that said: “BRING BACK PORTNOY.”

“It was wonderful, hilarious moment,” Roth recalls. “I actually thought about it for rest of walk: Why don’t I do that?”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.