The time has come for us to acknowledge the dirty little secret of Tisha B’Av: the destruction of the Temple was one of the best things ever to happen to the Jewish people.

Let me explain. A few months ago, I was meeting with a talented and committed Jewish community professional, and mentioned the famous Talmudic Aggadah (story) of the Oven of Akhnai. In the Aggadah, God attempts to intervene in a Halakhic dispute—and then is told by Rabbi Yehoshua, quoting the Torah (Devarim 30:12) that the law “is not in heaven” and that the Holy One should kindly butt out. The Talmud reports that God laughed and said, “My children have defeated me.”

My interlocutor was stunned, elated, and not a little upset. “I went to religious school for 10 years,” she told me. “Why haven”t I ever heard this?”

Though sorely tempted to recite the familiar litany of complaints about Jewish education, it dawned on me that my friend might never have heard the story because the Talmud has virtually no place in the Jewish liturgy or holy day cycle. Our people’s greatest legal and literary achievements remain hidden to us. That has to change.

What does this have to do with Tisha B’Av? Everything.

We mourn the Temple’s destruction on Tisha B’Av, but had the Temple actually survived, it would have meant the destruction of the Jewish religion. Our religious and spriritual practices would have centered not on Torah, but rather on bloody sacrifices of bulls, lambs, and goats on the Temple altar. Can anyone seriously argue that such practices represent the way of uplifting the soul and approaching God?

Perhaps more importantly, survival of the Temple would have deprived us of the extraordinary achievement of rabbinic Judaism—a religion vastly superior to the Priestly cult that preceded it.

Judah Ha-Nasi only decided to compile the Mishnah when it became clear that the Temple would never be rebuilt. So had the Temple survived, there would have been no Mishnah. No great tradition of scholarship and learning. No Pirkei Avot. No Tosefta. No Talmud. No Rashi. No Maimonides. No Ramban. Only a lot of dead, bleeding animals.

Rabbinic Judaism, and the texts, institutions, philosophies, and traditions accompanying it, constitute not only one of the greatest achievements in the history of human civilization, but also one of the greatest paths for connecting with God. The triumph of the rabbis represented nothing less than the divine spirit entering the minds, hearts, and souls of the Jewish people. In this light, mourning the Temple’s destruction is entirely misplaced: the event represents the Jewish people’s maturation into a closer, more adult relationship with the Holy One. It is not a tragedy, but more akin to our people’s Bar Mitzvah.

So does that mean that we should abandon Tisha B’Av? Hardly. Instead, we must do what generations of Jews—inspired by the example of the rabbis—have always done so brilliantly: re-interpret and deepen the tradition. We must use the occasion of breaking the Tisha B’Av fast to celebrate the new birth of Judaism in the wake of the Temple’s destruction. We must, in short, reclaim Assarah B’Av.

It requires little imagination to develop the Assarah B’Av celebration. First, of course, there must be food—what else for a break-fast? A very short service could follow, but one that highlights the meaning of the day. It will not abandon the tradition, but recover and empower it. One could start with this Aggadah:

Rab Judah said in the name of Rab, When Moses ascended on high he found the Holy One, blessed be He, engaged in affixing coronets to the letters. Said Moses, “Lord of the Universe, Who stays Thy hand?” He answered, “There will arise a man, at the end of many generations, Akiba ben Joseph by name, who will expound upon each tittle heaps and heaps of laws.” Lord of the Universe,” said Moses; “permit me to see him.” He replied, “Turn thee round.” Moses went and sat down behind eight rows [and listened to the discourses upon the law]. Not being able to follow their arguments he was ill at ease, but when they came to a certain subject and the disciples said to the master “Whence do you know it?” and the latter replied “It is law given to Moses at Sinai” he was comforted. Thereupon he returned to the Holy One, blessed be He, and said, “Lord of the Universe, Thou hast such a man and Thou givest the Torah by me!” He replied, “Be silent, for such is My decree.” (Menachot 29b).

What a glorious gem this is! Even Moshe Rabbeinu must sit in the back row of the Mishnaic Academy, but in the end he understands the key point: Torah is not something given once and frozen in time. Instead, Torah constantly evolves and changes through the creativity, imagination, and piety of Israel. Assarah B’Av joyously commemorates just this creativity, imagination and piety. And such joy is particularly fitting because God Himself wanted it that way: He could have decreed all of Torah in one instant, but chose not to do so in order for humanity to discover truths for themselves.

Maimonides knew as much. He explains in chapter 32 of Book III of Guide of the Perplexed that God did not institute sacrifices because He actually wanted sacrifices; far from it. Instead, the point was to eradicate idolatry little by little, but had He simply told the Israelites to worship through study, prayer or meditation, they would not have understood these instructions and could not have followed them. Sacrifices were not ends in and of themselves, but rather designed to foster the Israelites” spiritual tutelage: in the same way that God did not lead the children of Israel directly to the Promised Land, He did not lead them directly to the best form of worship. The ideal form of worship, Maimonides suggests, would be silence, although he doubts the human capacity to remain focused on divine unity just through silence. Sacrifices, however, are no longer necessary.

It thus stands to reason that along with the Aggadah, the selection from the Guide would form the core of Assarah B’Av observance. But how would we read such texts? By chanting them, of course. Music here represents an obstacle and an opportunity. There is a Torah trope, a Haftarah trope, an Aicha trope, a Shalosh Regalim trope—but there is no Aggadah trope. It is high time to develop one. So, too, with a Rambam trope, which in the case of the Guide will present an additional challenge since the Guide is in Arabic. We should welcome this challenge, as chanting the Guide in the original demonstrates how Judaism both influenced and was influenced by the cultures around it. This is an additional message of Assarah B’Av: syncretism is not to be feared, but embraced.

How to close the service? The obvious text is Kaddish Rabbanan, or the Rabbi’s Kaddish, which forms a key part of many services but remains unknown to many modern Jews. It is like the standard Reader’s Kaddish, but with this extra paragraph.

To Israel, to the teachers,

their disciples, and their disciples” disciples,

and to all who engage in the study of Torah,

in this holy place or elsewhere,

may there come to them and you great peace,

grace, kindness and compassion,

long life, ample sustenance

and deliverance from their Creator in Heaven—

and say: Amen.

Nothing could be more appropriate to commemorate the birth of Rabbinic Judaism.

And then? More music. More food. More dancing. For we should not merely observe Assarah B’Av, but celebrate it. Celebrate the towering achievement of our ancestors. Celebrate their rescue of Jewish spirituality. Celebrate their connection with the divine presence. And finally, celebrate how that presence can, after thousands of years, come into our daily lives, again and again, l”dor va-dor, and forward into all of time.

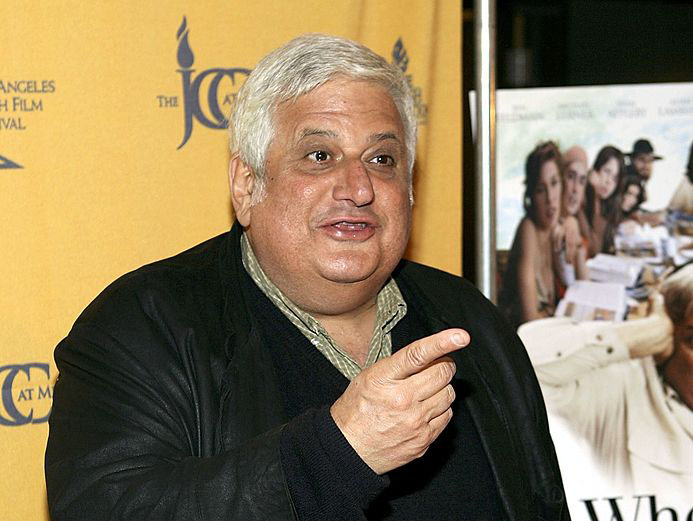

Jonathan Zasloff is Professor of Law at UCLA and a rabbinical student in the ALEPH-Jewish Renewal Ordination Program.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.